Humanity in the Age of AI

For as long as we’ve walked this earth, two things have set us apart from other species.

- We are Makers

- We are Storytellers

From the first spark of fire to the first word etched on a cave wall, we’ve been shaping the world around us, and giving it meaning. We built tools to survive, machines to thrive and societies to dream together.

The hammer gave us homes.

The pen gave us history.

The printing press gave us knowledge.

With each invention, we’ve painted the skies with stories, and passed them down generations. Whether it was folklore, legends, paintings or films, we’ve always needed more than just survival. We’ve needed expression. A way to make sense of the chaos.

Today, not much has changed. We’re still those tool-making, story-weaving creatures.

But something has shifted. Something substantial.

For the first time in our long, winding tale, we find ourselves staring at a tool so powerful, it might just be the last invention we ever need to make.

Artificial Intelligence.

The Birth of an Intelligence

Machine Learning as a concept was first born in the 1950s, when Alan Turing posing the famous question “Can machines think?”. With it came the idea of the Turing Test, a way to judge whether a machine could imitate human intelligence well enough to fool another human. Not long after, the term Artificial Intelligence was coined at the Dartmouth Conference.

But AI as we know today, Generative AI started making waves only in 2020, when tools like ChatGPT, DALL·E and Claude exploded into public use. Suddenly, people had access to deep learning tools that were only confined to labs.

The early days of AI were clumsy, fascinating and weirdly beautiful. AI Dungeon, based on GPT-2, let people roleplay with a text AI. It was chaotic, unpredictable, and fun. DALL·E 1 could generate images from prompts like “an armchair in the shape of an avocado”. Quirky stuff, more art project than product.

But then came the explosion. DALL·E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion turned text-to-image into an art movement overnight. GPT-3.5 and then GPT-4 could write essays, poems, code and whole websites. Suddenly, everyone, from designers and coders to your uncle on WhatsApp was dabbling in generative AI.

And so a new age was born.

The Camps

Right now, AI feels a lot like the early internet. Full of excitement, fear, confusion and limitless potential. Nothing is set in stone and everything seems possible. Key players in the sector, like OpenAI, Anthropic, Google and Meta are still oscillating between being cautious idealists or breakneck capitalists.

And the rest of us? We’ve split into camps. Three, to be precise:

The Hype: “This Changes Everything”

This camp sees AI as the new electricity. The steam engine of the digital age. It’s comprised of tech bros building 5 startups a week using the same API, designers creating entire brands in an afternoon and teachers rethinking pedagogy overnight.

These are people who are curious, experimental and beautifully optimistic. They ask questions such as, What if we can use this for good? What if this finally levels the playing field? What if this is our renaissance?

The Panic: “We Are Doomed”

Fuelled by years of dystopian sci-fi movies, the panic camp believes that AI is a disaster waiting to happen. They look at the same tech demos and see broken systems, stolen art, misinformation, surveillance capitalism, job loss, algorithmic bias and an accelerating sense of “we are not ready for this.”

Some express it through policies and protests. Others through poetry and art. But at its core, this camp simply asks, Why is no one putting on the brakes?

The Nonchalance: “What’s for Lunch?”

The third camp might be the most fascinating , because they barely react at all. To them, AI is another buzzword in a long line of tech trends. Blockchain, crypto, NFTs, the metaverse. Remember those?

Call it digital fatigue. Or call it a survival mechanism.

They’ll use AI if it helps. Maybe to generate an email or do a quick search. But they’re not philosophizing. They’re not scared. They’re not impressed. They’re just… busy. Paying bills. Making lunch. Living.

But this blog isn’t for the enthusiasts or the skeptics.

It’s for those standing in the middle.

For the hopefuls in the panic camp, trying to believe.

For the realists in the hype camp, starting to wonder.

For anyone asking the quieter, harder question: Where is the line between good AI and bad AI?

Let’s walk toward it. Together.

The Great Unreality

There was a time when the Internet felt like a vast, living city. Each corner, market, post, photo created by people. You could trace a photo back to its camera. A story back to its voice. A recipe back to a grandmother somewhere.

It felt… human.

But now, it’s starting to feel like a simulation. Full of echo chambers. Devoid of humans. A beautifully rendered illusion.

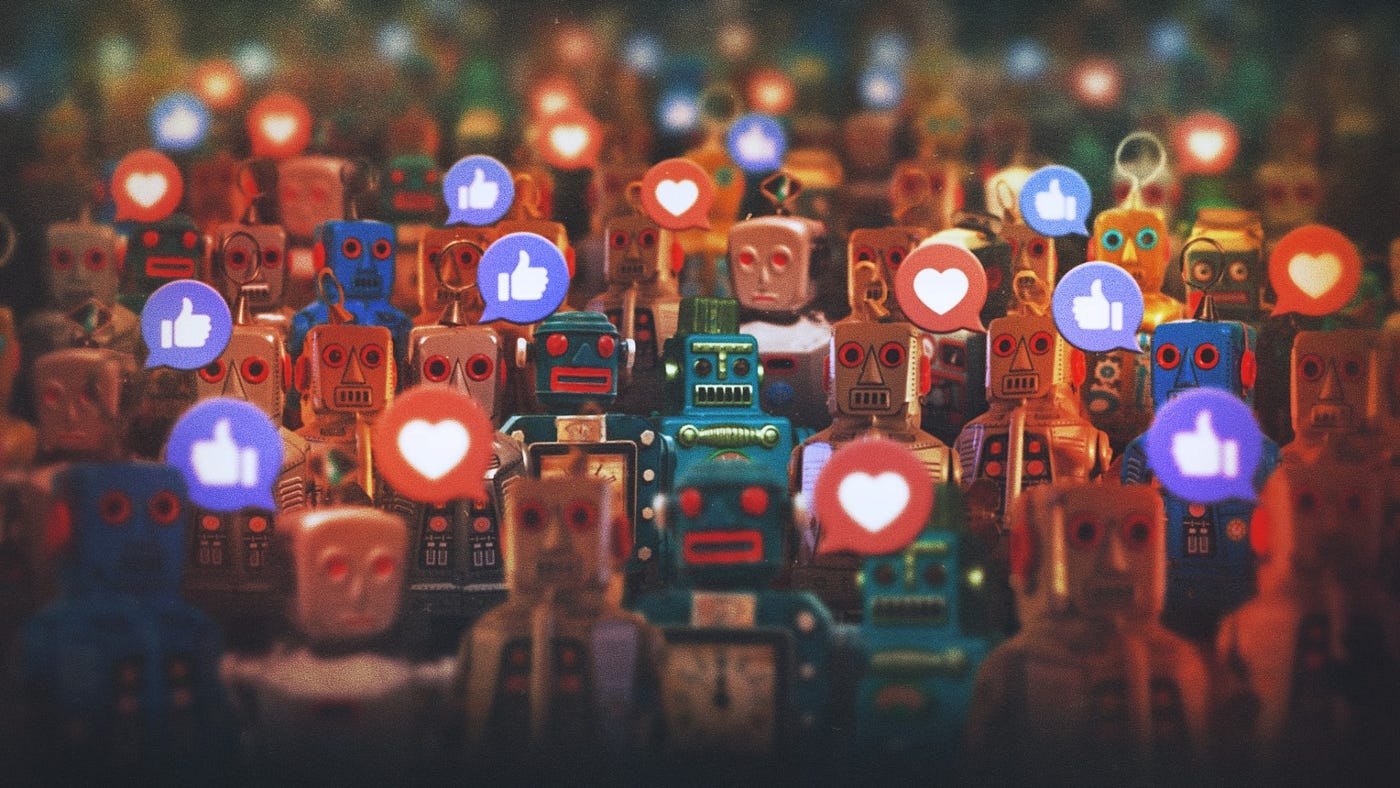

Some have even floated the eerie conspiracy theory: The Dead Internet Theory.

That everything we read, watch or engage with is no longer made by humans. That we’re browsing a ghost town animated by algorithms.

For years, it was just that. A conspiracy. But today, it’s not so easy to dismiss.

Twitter and YouTube are flooded with bot armies, pushing spam and agendas for the highest payer. Faceless websites churn out content by the second, not for humans, but for search engines.

Pinterest, once a gallery of human creativity, is now riddled with images of things that never existed. Chairs never touched by a carpenter, gardens that were never watered and illustrations that had no messy sketches to begin with.

When you saw a dish online, you used to wonder who made it. Now you wonder if it was made at all.

The internet was supposed to be a hopeful place, where messy, imperfect people could meet and make things together. But somewhere down the line, we traded soul for scale. Connection for content. Meaning for metrics.

Let’s take a closer look at 6 challenges that AI has introduced, and attempt to make sense of a new world.

1. The AI Slop

Pick any social media. Any corner of the internet where you once gathered to be inspired, entertained and informed. Have you noticed something different?

You’re not alone.

Social feeds that once reflected slices of real life now feel like conveyor belts of something else entirely.

This is AI Slop — a term used to describe the digital equivalent of junk food. Mass produced and nutritionally void. Mindless attention grabbing content made with AI with the sole purpose of maximizing interactions. Videos of cats doing human work, of pizzas turning into humans and clickbaity “life stories” that never actually happened.

This is content that is very obviously AI, but it just needs to feel engaging enough to trap your scroll. And it works, because our attention, fragmented and fatigued, doesn’t always pause to ask if what we’re watching was made with care or just optimised for attention.

Recently, Youtube had to step in, tightening its creator policies to push back against the growing flood of creators looking for “easy money”.

It’s not just video. Even image search is slowly being overrun.

Try Googling “baby peacock.”

Nearly half of the images are AI generated. In fact, to find something real, we have to time travel — to set our search filters to 2022 or earlier.

2. Misinformation

When fake videos first entered the public eye, experts warned about the dangers they posed for society. As political philosopher Hannah Arendt cautioned:

“The biggest danger may not be that people believe false information, but rather that they stop believing anything at all.”

Because once you can fake a video perfectly, truth itself becomes negotiable.

And now, with generative AI, we’ve stepped squarely into that danger zone. Misinformation is being spread at a much larger scale. Fake videos of political leaders saying things they never said. AI generated recipes that look mouth watering but are nutritionally dangerous. Fitness hacks, crisis footage, deepfakes designed to spread confusion.

While some of us are used to spot the tells, most aren’t.

Our parents.

Our grandparents.

Even our more trusting friends.

Like the viral video of a kangaroo holding a boarding pass, being denied entry into a flight as someone’s “emotional support animal”. It made the rounds, it got laughs, and it fooled more people than it should have.

In the age of virality, that’s all it takes.

The recent Iran-Israel conflict became a disturbing milestone. Perhaps the first war where AI warfare played a starring role. Fake bombings and propaganda videos created with the intent to falsely justify actions and to rile up populations and governments.

We’re still at a point where we can recognise AI content. How hands have too many fingers, gymnasts have too many legs, and how clocks stubbornly default to 10:10, because that’s what the data models were trained on.

But that window is closing.

The big players, OpenAI, Meta, Google are all sprinting towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). As models improve by the week, we inch closer to a time where fake and real is indistinguishable.

AI is changing the understanding of “objective reality” for many of us. Because if any video could be fake, what becomes of evidence? When any voice can be cloned, what becomes of trust?

And when we reach a point where any and all reality is possible, what will be the truth then?

3. Unemployment

First it was a few job titles.

Copywriters. Coders. Illustrators.

Then it was whole departments.

Photography, CGI, Research, Legal, HR.

The changes came quietly at first. A tool here and a shortcut there. But looking back at the past 5 years, it’s not hard to see the pattern.

Social media now brims with influencers who don’t eat, sleep or age. They never have days off. They never ask for raises. They model, promote and travel the world in pixel perfect sunsets, all from a server room. And brands are lining up, because why pay for a plane ticket, when you can license a fantasy?

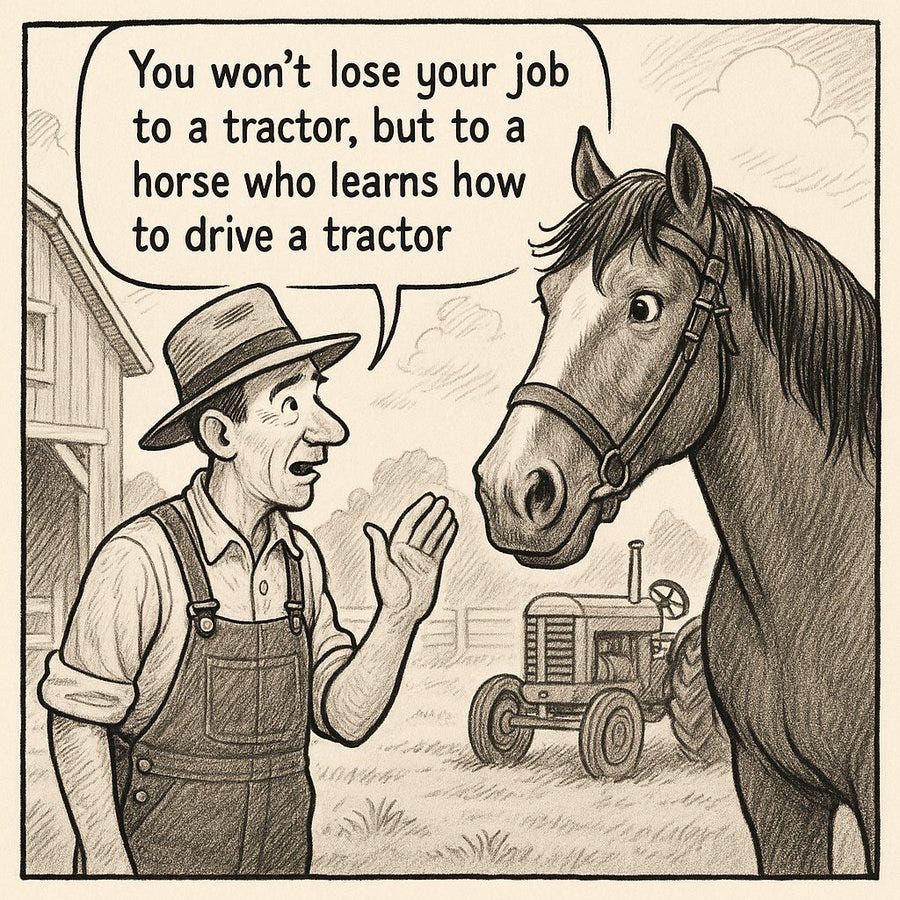

Speaking at the Milken Insitute’s Global Conference 2025, Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia said,

“You are not going to lose your job to AI, but you are going to lose your job to somebody who uses AI”

But is it even possible to compete in this race and still remain human?

Even companies that once celebrated human creativity are now shifting gears.

Duolingo, in a recent announcement, said that it would be “AI first” to produce more language learning content. All the while, the company quietly laid off hundreds of writers and contract story creators last year. The math is simple. More content, less cost.

Even Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke sent a memo to employees saying that before they ask for more resources, teams must show why they “cannot get what they want done using AI.”

Across industries, this is becoming the new normal.

Take film. What once took teams of writers, designers, directors, crew members, editors, actors, costume designers and months of coordination, can now be simulated in a fraction of time, and budget.

The same goes for music. Lyrics, melodies, even voices to sing them can all be generated with a prompt. Spotify and YouTube are now filled with AI albums that sound good enough, and cheap enough to scale endlessly.

And while some argue that AI will “create new jobs,” the transition isn’t symmetrical.

We’re losing careers in weeks.

We might gain new ones over years.

If machines can do what we do, faster, cheaper, and without complaint…

Then what exactly is the value of human work?

And more hauntingly, what happens to us when we no longer feel needed?

4. Art

This quote by the author Joanna Maciejewska has been going viral for quite some time now:

“I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes.”

It’s simple. But it hits deep. Because that’s the hope, isn’t it? That technology would free us, not replace us.

This sentiment has seen a lot of support from the art community recently after seeing how many Language and Image generation models were found to be trained on centuries worth of human literation and art. Without credit or consent.

A joint lawsuit, Disney and Universal are suing Midjourney accusing it of mass copyright infringement. Their image results contained recognizable characters. Shrek, Minions and characters from Star Wars. Clear violations of intellectual property.

But what about the artists who aren’t backed by big studios or legal teams?

What happens to the small creators whose work gets absorbed, unnoticed into these models? What happens when someone generates a fake wood carving based on data trained on a real wood carver’s work, and then gets all the likes, shares and recognition?

We are in an age of quick fixes and shortcuts. We are valuing speed more than hard work. Always in pursuit of the next big AI tool.

There was a case where Sarah Snow, a content creator known for her beautiful video captions, shared how people often ask her: “Which App she uses to do the captions on her videos?”

They assume it’s automated. What they don’t see is the hours spent choosing fonts, refining layout and crafting words that actually mean something. Real art, she reminds us, takes time. Effort. Heart.

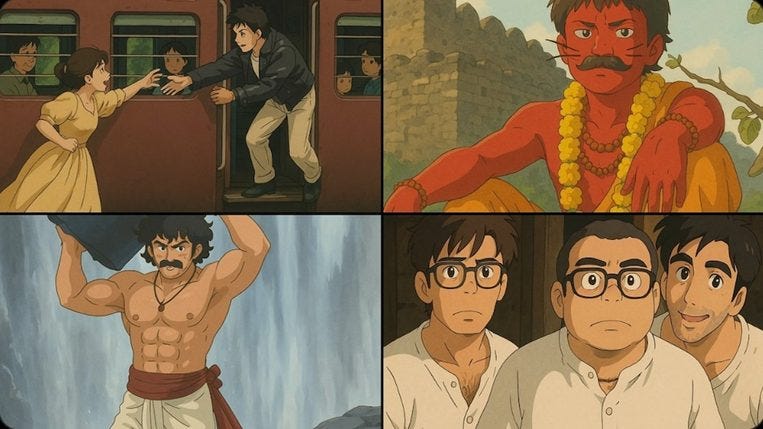

But we’re living in an era that values convenient art more than real art or artist. Nothing reveals this more than the recent “Ghibli trend”.

After OpenAI’s GPT4 image gen model dropped, timelines flooded with Ghibli-fied portraits. At first glance, it felt charming. Nostalgic. But if you give it a thought, the irony stings.

Studio Ghibli was built on slowness. On detail. On Hayao Miyazaki’s painstaking devotion to storytelling. Drawing thousands of frames by hand, creating entire worlds with care and refusing to rush even a single second of animation.

The Wind Rises, a fictional biography film by the Studio Ghibli features a four-second crowd scene that took animator Eiji Yamamori 1 year and 3 months to complete.

Rather than a tribute to Ghibli films, these AI images are against the very philosophy that Hayao Miyazaki lived by.

And so we ask.

If art becomes effortless, do we still value it? If beauty comes instantly, do we still respect what it took to achieve it?

5. Crime

The digital world was already haunted by demons.

Deepfakes.

Revenge porn.

Stolen Identities.

But with AI models, miscreants now have renewed tools and powers. Anyone with a few clicks and a prompt can replace a face. Generate explicit images without consent, without trace and without remorse.

This raises all sorts of ethical, moral, legal and social concerns. Our policies and judiciary are yet to catchup to these new technologies, and might keep playing catchup for a long time.

So for now, we are at the mercy of platforms whose primary allegiance lies not with people, but with profit.

There’s another menace insidiously brewing beneath the surface. The erosion of privacy.

Teenagers today are turning to chatbots for comfort and therapy. Not because they get the best advice. But because these inanimate bots are free of human judgement and free of humanity. They feel more comfortable sharing their intimate thoughts with them. And the bots listen. Patiently, passively.

But AI models are increasingly trained on the very data we share. Chat’s photos, confessions. Every message, every vulnerable moment, is quietly teaching the machine how to know us better. To profile us more accurately.

Do people know this?

Do they care?

Does it really matter?

If privacy is given up willingly, and our thoughts can easily be manipulated and mirrored back at us, where do we draw the line between advice and coercion?

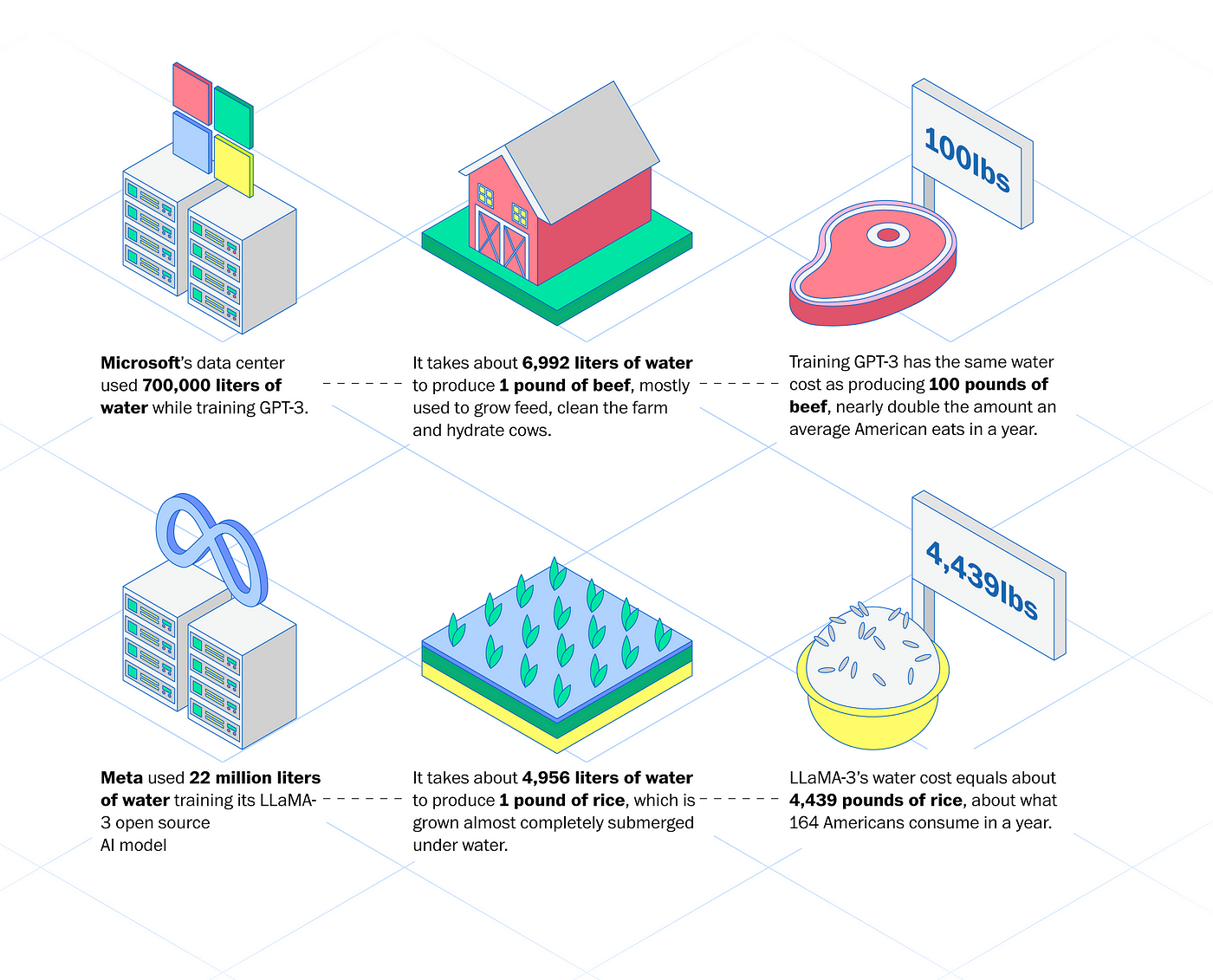

6. Environment

Of all the effects of AI, this might be the quietest one. Not because it’s small. But because it’s harder to see.

We often imagine AI as a floating brain in the cloud. Weightless, clean, abstract. But behind every prompt, every image, every line of generated code is a very real, very hungry machine.

One that needs computation. And power. And water.

The servers that keep AI running, that make Claude respond, that render Midjourney’s images, require massive data centres. And those centres consume energy at staggering rates.

A research due to be published later this year estimates ChatGPT gulps up 500 milliliters of water every time you ask it a series of 5 to 50 prompts or questions. The range varies depending on where its servers are located and the season. But it underscores a point: tens of millions of users chatting with AI could be silently draining lakes and rivers.

The energy footprint is similarly huge. Training one large AI model can consume hundreds of megawatt-hours of electricity. Running them in production adds even more ongoing draw. It’s telling that Google’s environmental report admitted its carbon emissions rose 48% in 2023, citing AI and data centers as a major driver.

How do we plan to sustain this technology as it keeps progressing, getting better and needs more and more resources? And all of it drawn from a planet that is already stretched thin?

We talk of AI as though it floats. But it’s tethered, tightly, to the Earth.

To lithium mines and power grids. To freshwater reserves and fossil fuels.

So we must ask ourselves:

“Can we build a future where the intelligence we create doesn’t come at the expense of the home we live in?”

“Should we?”

The Seduction

We know the problems. We’ve read the warnings. We’ve watched the videos, shared the articles, whispered the fears.

And yet… we still use it.

Why?

Because AI offers us something intoxicating: the illusion of effortlessness. Creation without the mess. Output without the process. Genius without the grind.

Why spend hours crafting the perfect sentence, when a prompt can do it in seconds? Why wait for inspiration when you can autocomplete it?

We are creatures of convenience. And AI speaks our language fluently.

It flatters us. It makes us feel smarter, faster, more capable. It turns us into mini gods of production. Build an app in one click. Design a website in one prompt. Animate a story in while you have a meal.

We tell ourselves — it’s just a tool.

It’s just helping.

It’s saving time.

It’s giving access.

And sometimes, all of that is true.

But beneath that truth is a trade: one small piece of your creative soul, exchanged for speed. And so it keeps seducing us, like the Sirens in the Odyssey. With answers that are just good enough.

We keep using it not because we are blind to the flaws. But because we no longer remember what it felt like to struggle for beauty.

So yes, AI is seductive.

But maybe the question isn’t why we use it.

Maybe it’s why we stopped believing in the value of doing it ourselves?

The Hope

Let’s flip the coin.

Because despite the noise, the fear and the spiraling questions, AI isn’t all dark clouds.

It has been pretty helpful in medical research break throughs, from protein structure predictions to drug discovery.

It is giving sight, or something close to it, to the visually impaired, allowing them to navigate the world with newfound independence.

It is teaching children in new and interactive ways. For example, Khan Academy’s “Khanmigo” uses GPT-4 to guide students through problems Socratically, never giving away the answer but prompting the next thought.

It is helping researchers and students build things once reserved for professional labs. Sign language translators, health apps, assistive tech. Ideas once stuck in minds and notebooks, now becoming prototypes.

A team of undergrads used open-source AI to develop an app that listens to a person’s cough with a smartphone microphone and predicts if it’s likely asthma, pneumonia, or just a common cold. A pocket diagnostic tool that could be especially useful in low-resource areas.

It is lowering the entry barrier for storytellers too. Filmmakers no longer need blockbuster budgets to tell stories that move hearts. Game developers can focus on character, plot and emotion, while AI handles the grunt work.

And perhaps, most magically, we’ve started to talk to our machines. Not in lines of code, but in the language of desire, of imagination:

“I want a website that feels like a forest.”

“I want an app that helps my grandma remember her medicines.”

“I wish my game character could fall in love.”

This is new. This is beautiful.

So, there are clearly good things that have come out of AI technology. So we are faced with the moral dilemma.

“When is AI use ethical and when is it not? Where do we draw the line?”

The Line

As a design studio, this is a question we’ve had to confront almost everyday.

As creatives, we use these AI tools.

As a future forward design agency, we always stay updated.

As innovators, we experiment and try out new things all the time.

So we have spent a good amount of time discussing, deliberating and arguing about the ethical use of AI within our teams. And we’ve come to a simple test.

It’s not about the output. It’s about the intent. Is the intent to aid you? Or is it to make the AI do it for you?

Is the AI assisting your creation?

Or is it creating for you?

Is it helping you think?

Or is it thinking for you?

Is it helping you tell stories?

Or is it telling your stories for you?

Is it the hammer in our hand?

Or is it the hand itself?

We think there is a fine line, and once you see it, it’s hard to unsee.

AI should help us. Not make us helpless. And there are real consequences when we cross that line.

A recent MIT study found that using ChatGPT led to decreased brain activity and cognitive development in students. Not because AI is evil. But because we’re outsourcing the act of thinking to it.

So every time we design, we ask ourselves:

- Are we still the Makers?

- Are we still the Storytellers?

Final Thoughts

People often say AI is just another technology. That the internet too, was ridiculed and feared in its early days. That every great invention faces its share of backlash.

But AI is different.

This might be the first, and very possibly the last invention that doesn’t just change how we live, but what it’s means to be alive.

Because if we hand over the act of creation, the joy of discovery, the journey of struggle and the power of thought, if we lose the “labour” from our “labours of love”..

We risk losing purpose.

Just look to the “Rat Utopia” experiment. A world where every need was met. Every struggle removed. And with it, the collapse of motivation, identity and meaning.

We were not wired for passive perfection. We were wired to strive. To build. To stumble and get back up again.

We need to equip ourselves with AI. Not hand over the reins.

Because like every technology that came before, the true nature of a tool is determined by how we use it. AI may be the pen. But we must still write the story ourselves.

So, what does the future look like?

Maybe we’ll use AI for good and propel our civilization towards peace and prosperity. Maybe we’ll overlook the dangers and submit to our AI overlords.

We’re only human, after all.

PS: This piece was conceptualised, written and illustrated by humans at Studio Carbon with AI as an assistive tool for ideation and research.